Photographer Troy Paff joined Tusker Trail in Mongolia to capture the beauty of the Altai Mountains and show how the Tusker crew and local nomads help make this wild trek such an incredible experience. The following photographs and commentary originally appear on instagram.com/troypaff.

Altai Tavan Bogd: Our objective, now visible on the horizon.

The road to Ölgii, hour five. Desert has given way to steppe, steppe to marsh, and back again. While the road has never been more than a random array of rocky dirt tracks, at its worst it disappears altogether—such as at these marsh and river crossings. At 10:30 pm it is getting dark. Still more than an hour from our camp, our driver, Ada drives faster than ever to make the most of what little daylight remains.

Ölgii ger camp. Tusker head Eddie Frank at the end of a long but productive prep day. Despite the jet lag, all gear is ready to go. Tomorrow’s project: buying the supplies to feed two dozen people for a week on the trail.

Alex Minja, chef supreme. I first met Alex on Tusker’s Kilimanjaro climb where he astounded me with his resourcefulness and endurance. Trained by chefs from the Culinary Institute of America, Alex brings to the extreme wilderness an uncommon ability to create something from nothing, and his meals are critical to the morale of trekkers that may be experiencing the backcountry for the first time. At home in Tanzania Alex climbs Kili regularly and with aplomb. His personal best is 11 hours round trip … Without the requisite food, tents, and kitchen equipment, of course. Despite a language barrier, on this expedition in Mongolia, his local team learns a distinct professionalism from this focused and gracious man—as well as some catchy Kilimanjaro songs.

Master horseman Karbai with ‘Lunch Camel,’ the beast of burden who will accompany the client team and transport a midday meal for some twenty people.

Morning in Altai Tavan Bogd. We are at the headwaters of Western Mongolia. The Alexander and Potanin Glaciers are this source, and from the vast amounts of exposed scree and displaced earth that is visible, it is clear that these prehistoric glaciers are melting. Unofficial numbers place the loss of ice depth at 1.5 meters per year, which translates to a significant lateral retreat: Our older horsemen recall a time when the glaciers filled the valley.

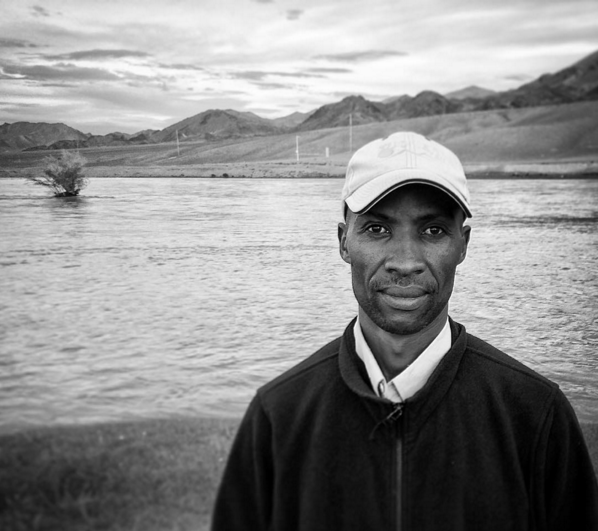

Dosjan: Computer programmer, entrepreneur, guide, and expert horseman. I learned more from watching his form than from any riding lesson I’ve been given.

‘Stone men’ or markers placed by prehistoric inhabitants of the Tsagaan Gol. The area is littered with such art, as well as with pristine stone etchings of the local wildlife and its ancient inhabitants.

The water collector of a nomadic family. I saw this child from a distance, alone in a shallow river in her boots, tirelessly filling bottles by capturing the current and pouring one bottle into another. This adorable little girl took a bit of cajoling to coax a smile, but only a little. Her task at last complete, she thought it quite funny that I would be interested in what she was doing. As she shuffled away, dragging the jugs behind her and giggling, I wished she knew how this brief interaction had made my day.

Toroo, a nomadic Tuvan boy. Not yet a teenager, he is already in charge of his family’s herd of hundreds of goats.

Dusk falls over high camp at Alexander and Potanin Glaciers

This is how the Mongolia adventure ended.

All of the client trekker/riders lined up on one end of a small clearing, while at the other end the local horsemen, cooks, and guides faced them in their own line. This was the time for farewells, thanks, and gratuities for a wonderful experience had by all. Each client had an envelope with the name of a crew member written on it. Inside was an evenly apportioned tip pooled from the entire client group. In random order each gentleman’s name was spoken by a client and his envelope thus presented, typically resulting in a hug, high five, waltz, or tickle fight. What suddenly and unexpectedly carried the weight of heartfelt ceremony just as quickly evolved into an iPhone dance party on the high plateau.