International:

North America:

Menu

International:

North America:

- Home

- Kilimanjaro Climb

- Kilimanjaro Planner

- Other Treks

- About Us

- Dates + Prices + Booking

- Contact

International:

North America:

International:

The Trek

18 Days

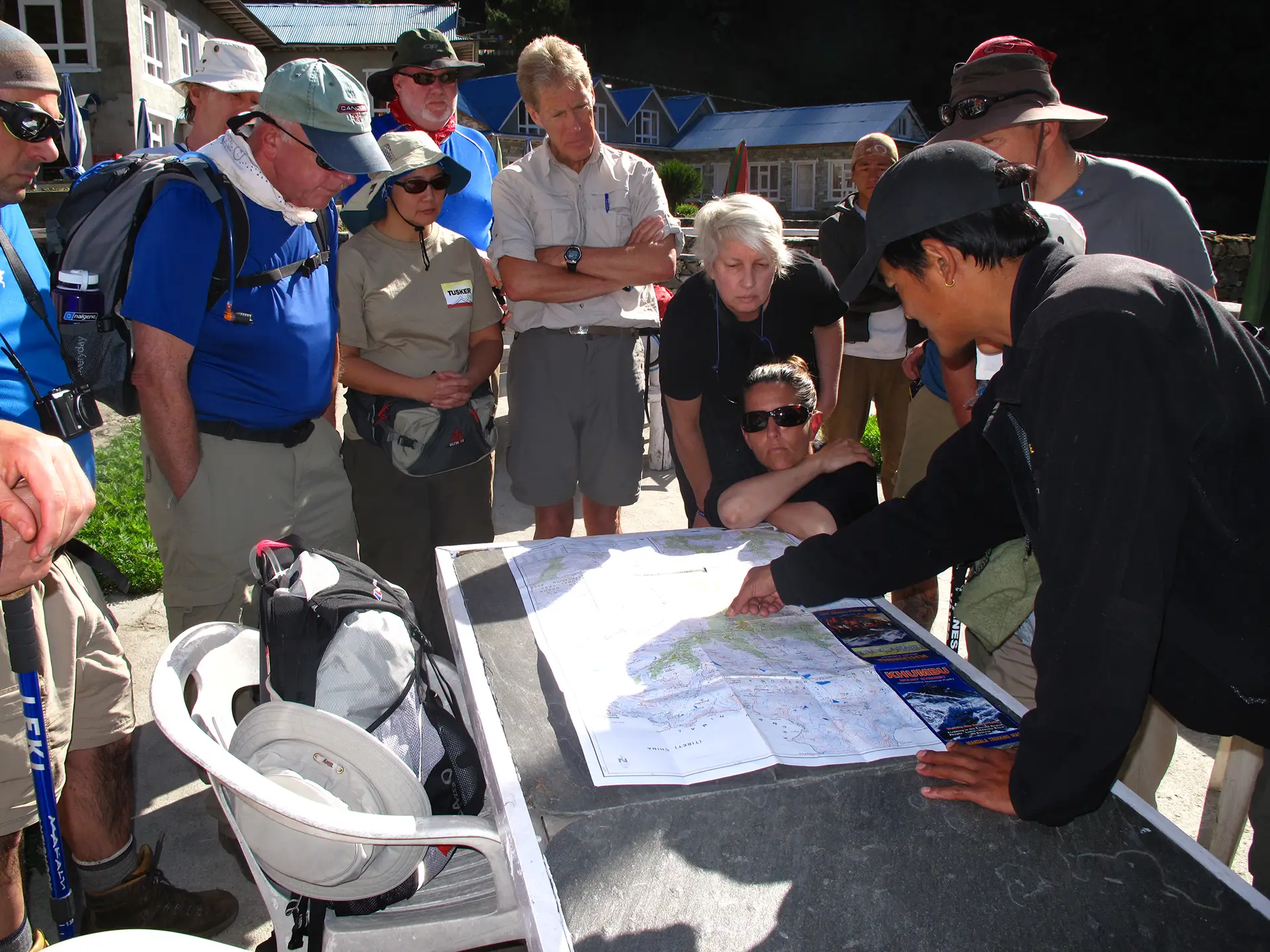

At 17,598-ft/5,634-m, Everest Base Camp is the highest of the world’s Seven Summits. This trek is a true adventure, with every step taking you deeper into the mystical Himalayas. Tusker Trail flies in two of our high altitude medically trained guides from Kilimanjaro who monitor your health and safety during your trek. No other company offers this safety net.

You are led by our expert Sherpa guide who provides a unique insight into Nepal and the Himalayan mountains, while being supported by our professional Sherpa support team every step of the way. Our of Nepali chefs will provide you with delicious meals that combine western and Nepali styles.

Dramatic

Landscapes

The moment you arrive in Kathmandu, the excitement begins. Then, as you start your trek through the most dramatic landscapes on earth, you encounter a one-of-a-kind culture in one of the highest environments on earth. It’s transformative.

During your 18-day adventure, you journey through a world unlike anything else on the planet. Beginning in Kathmandu, up to the ancient Namche Bazaar and across to the hilltop Buddhist temple at Tengboche, with the monks chanting their solemn prayers, your journey through a fabled foreign land puts you in a state of awe and wonder.

As you approach Base Camp, you behold the most iconic peak in the world towering above you. Along the southeast ridge you can see the Hillary Step and the ominous Khumbu icefall. Gazing in awe, you soak in the majesty of the tallest mountain on earth.

The trek to Everest Base Camp was created many years ago by Everest climbers and a group of their friends for support. This is where they would base themselves to acclimatize before attempting the summit. Nowadays, the trek has become a highly sought-after pilgrimage to the foot of the great mountain and is hiked by thousands of people each year.

Each day on your trek is magical – an experience that stays with you for the rest of your life. You hike through spectacular landscaped and and get fully immersed in Sherpa village life. The Himalayas have the world’s highest peaks and will blow your mind, towering above you as you wind your way through the Khumbu valley to the base of the world’s most famous peak.

The Himalayas • Nepal

The Challenge

Tusker’s core values can be found at the heart of the Everest Base Camp trek – the adventure and the challenge. The awe of discovery and the thrill of journeying in a new land keeps you amped on this journey of a lifetime. The challenge of hiking to the highest places on earth, across hanging bridges, down steep valleys, and over majestic mountain ridges fires up your spirit in a primal way. Exploring this natural wilderness, while immersing yourself in an ancient mountain culture, is enough to overflow your bucket with exhilarating adventure. Your own voyage of discovery is here.

The Natural Beauty

Mount Everest has captivated people from around the world for decades. During your adventure-packed journey of a lifetime you hike among the world’s greatest peaks as you witness blankets of clouds covering the distant glaciers. Treading lightly on the hanging bridges, your trek will take you to a mystical Buddhist monastery perched on a lone hilltop. With each step you envelop yourself in an ancient culture that’s been in sync with nature for centuries.

A Life-Changing Experience

Your

Bucket List

Trekking to the foot of Everest in Nepal is the ultimate adventure. By creating your bucket list, you thrust yourself on a path of self-awareness, compelling you to discard your fears and go all-in. Of all the treks that Tusker runs, this concept couldn’t apply more than on our EBC trek. You detach yourself from your worries and fears, firing up your passion for life, and new encounters. You embark on a journey – on the inside, as well the outside, making a complete transformation.

Eclectic Lodges

You experience a myriad of lodges and hotels, all with great views that expand your mind, body and soul. Acclimatizing to the altitude and engaging the Sherpa culture are highlights of your trek, and your lodging plays an important part in your experience.

You arrive in Kathmandu, a city famous for its cultural wonders, where you begin your trek in an oasis, the Shangri-La Hotel, before your flight to Lukla. After landing in Lukla, you travel through the Khumbu Valley, staying at family owned lodges every night. They are all very basic, but extremely comfortable spots for a good rest after a tough day trekking. As you gain altitude, you surround yourself in the warmth of the Nepali people.

The Evolution of Tusker’s EBC Trek

In 2008, a friend of Tusker who had climbed the Seven Summits approached Amy and Eddie Frank, Tusker’s owners . He asked them to join him as the medical guiding team on his charity trek for the Make-a-Wish Foundation to Everest Base Camp in Nepal. They led 27 trekkers through remote Sherpa villages on a trek among the magnificent Himalayan mountains. This kicked off what was to become one of Tusker’s most exciting and challenging treks.

The foundation of Tusker’s trek to Everest Base Camp dates back to 1977, when Eddie Frank, on his search for adventure, led an expedition across Africa in British ex-army Land Rovers. Since then, he has made 33 crossings of the Sahara Desert and climbed Kilimanjaro 54 times. On one of those climbs, he met guide extraordinaire Amy Frank. They formed the perfect guiding team and have since led many wild expeditions for countless travelers to the far corners of the globe.

The Himalayan Mountains

The Himalayas is the most well-known mountain range in the world, extending across part of India, passing through China, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bhutan. The range includes the tallest peaks on earth, such as Makalu (27,838-ft/8,485-m), K2 (28,251-ft/8,611-m) and the big brother Mt. Everest (29,029-ft/8,848-m).

The Himalayas are also the source of many of the world’s great rivers, such as the Ganges in India, the Indus in Pakistan, and the Brahmaputra in Tibet, India & Bangladesh. While it is relatively young compared to most ranges – only 50 million years – its mountains are the tallest and most dramatic. The Himalayan climate ranges from tropical at the base, to perennial year-round, and snow, ice and glaciers at the higher elevations.

Flora and Fauna

The flora of the Himalayas is highly dependent on elevation and precipitation – tropical, subtropical, temperate, and alpine. Plants stop growing above the altitude of 18,864-ft/5,750-m, as this is the permanent snow line in the Himalayas. On your EBC trek you’ll enjoy the spectacular alpine forest landscape which gradually changes as you gain elevation to small shrubs, lichens, and mosses. The mountain range is also home to many mammal species, such as the Himalayan black bear, musk deer, snow leopards and martens.

Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay completed the first confirmed summit on May 29, 1953. They were part of the ninth British expedition to climb Mount Everest. The first documented attempt to summit Everest was in 1921. A British expedition led by George Mallory trekked over 400 miles across the Tibetan plateau to the base of Everest.

A fierce storm forced them to abandon their climb, but before they turned around, they discovered what appeared to be a possible route up to the peak. When asked by a journalist why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, he famously replied, “Because it’s there.” These days about 900 climbers reach the summit every year.

Getting Around

Trekking Seasons

Summer / Monsoon Season

June, July and August is the monsoon season. Very few people trek at this time. There is no flora blooming, and the rain can cause hazardous trekking conditions.

Fall – Tusker’s Trekking Season

September, October, and November are the peak months for EBC trekking, and this is when we run one of our departures. The monsoon is over, and the sky is usually crystal clear. This is a great time of the year and sees the most trekkers. The daytime temperature is comfortable, however the nights are a bit colder, but you’ll be ensconced in a warm sleeping bag.

Winter

In December, January and February there are very high winds. The nights are cold and days shorter. While trekking to EBC is still possible, we don’t trek at this time due to the cold temperatures.

Spring – Tusker’s Trekking Season

March, April and May close out the long winter and the entire Everest region comes alive once again. We trek during the spring, as this is when you get to rub shoulders with climbers who are just coming down from the summit of Everest. The excitement is palpable. The sky is clear with a rich blue color and the flora and fauna awaken along the trails as new life stirs.

Photo Gallery