Synonym for Adventure

Kilimanjaro. Katavi. Aconcagua. Mongolia. Just a few of the remote global destinations Tusker Trail founder Eddie Frank has blazed new trails. Even more important is the fact that he hasn’t gone alone. For the last 30 years, Eddie has taken wide-eyed adventurers on his expertly guided treks to exotic destinations. And in the process, made their dreams – and his, come true.

A sincere, passionate, and focused individual, relentlessly striving to provide the best adventure possible, with a pure love for experiencing the unknown, Eddie Frank’s name is synonymous with adventure. But the burning question still remains – how did a quiet kid from South Africa rise to become the visionary founder of Tusker Trail?

My name is Raj Balu, and I found out the easy way. I got a chance to spend some time with Eddie at his home and business based in Lake Tahoe, and speak to the colleagues and customers who know him best. In the process, I got to learn what makes him tick.

Eddie’s Footsteps

The guy has experienced great adventures from an early age. Born and raised in South Africa, he not only took his first footsteps there, but also developed a deep connection to the people and the land. He speaks Swahili, Afrikaans, French and Spanish; and according to him, he’s still working on English. In his early teens, his family moved out to Los Angeles, and by the time he was 20, he had his sights set on a fabulous career. Eddie had plans to become a coveted National Geographic photographer. Not the easiest job in the world to come by. Eddie knew the harsh reality – for those jobs many are called, but few are chosen.

Around the same time, Eddie was becoming more and more obsessed with another passionate idea – he had always wanted to drive across Africa. When a close friend laughed at him and told him he could never do it, all his friend heard was Eddie’s laughter as he walked out the door.

Adventure Calls

By February 1977, at the age of 23, a serious adventure was calling Eddie Frank. As I asked him about it and he began to delve into the details, I could tell this was no ordinary adventure.

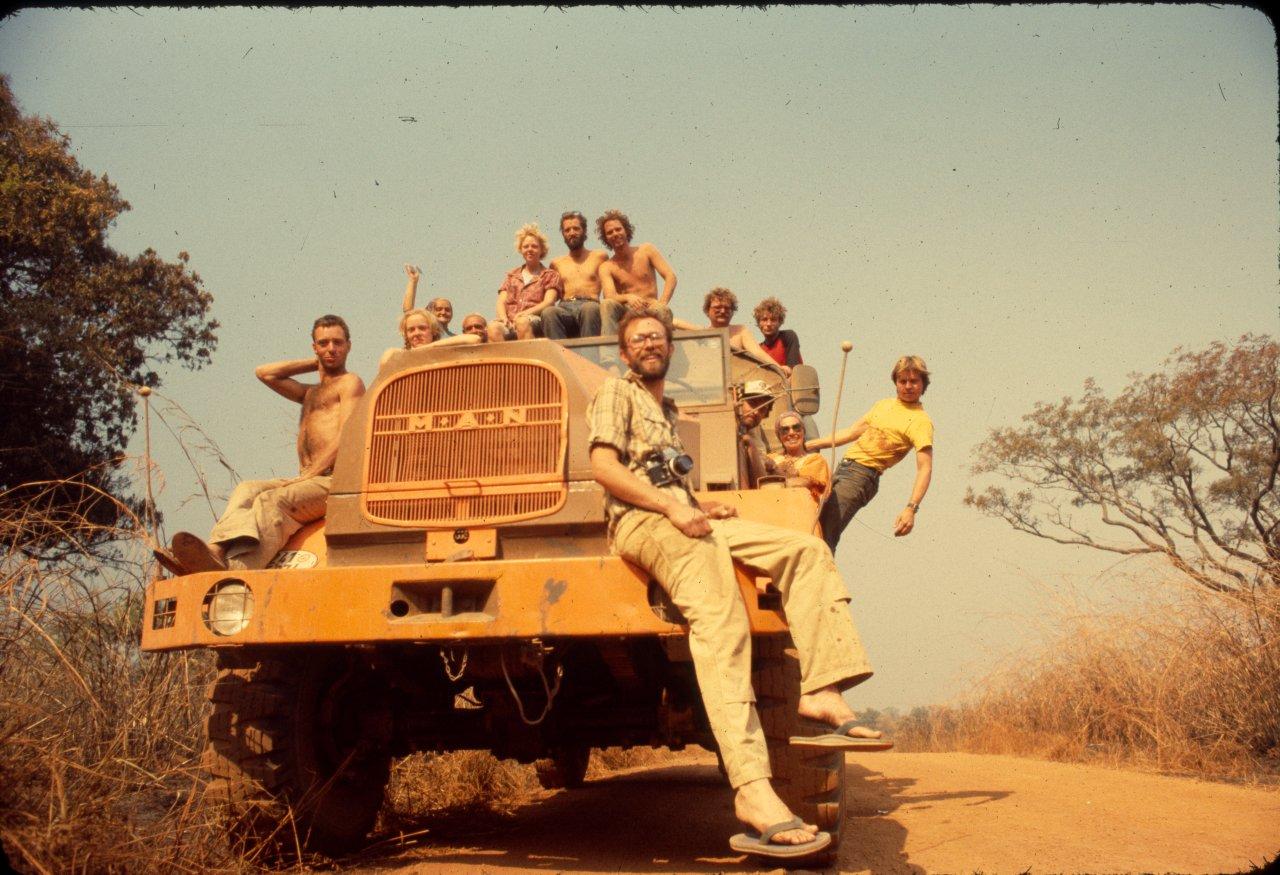

The first signs of Eddie’s adventure business were starting to emerge. He had found a business partner and marketed the idea of a fantastical road trip across Africa, and now he had a few dozen people paying him to take them. The trip got off to a great start, but in West Africa he had a falling out with his partner and they split up, each taking responsibility for half of the vehicles and half of the passengers. Not exactly the way Eddie had imagined things going, but a great learning experience nonetheless. Not long after, Eddie met Malcolm. As Eddie puts it, he was “a wild Englishmen who loved to fight. In his spare time he dabbled with bar brawls.” Eddie partnered up with him and began buying trucks from the German army and driving them across the Sahara desert into west Africa and selling them. A lucrative business, that is until Malcolm ripped Eddie off three years later and split.

Left with $500 and a strong will, Eddie began running adventure trips on his own. Over time he managed to find a constant stream of loyal followers who wanted to share his dream of seeking unknown destinations, and developed a solid understanding of what it takes to be the best adventure guide. What had started out as an adventurous lifestyle choice was actually turning into a profound and popular career.

Sky’s the Limit

Eddie is one of the early pioneers in the adventure travel world. He began doing it at a time when there were not many adventure travel outfitters. Today, Tusker Trail is a rousing success, and one of the top companies in adventure travel. Though there are a number of reasons for Eddie’s success, the number one reason is that he’s never stopped trying to refine and perfect his business and his outdoor skills. And he stays outdoors.

He takes great pride in his heels-on-the-ground approach to travel while keeping his eye out for the next remote destination. When it comes to his clients, he wants their sky to be the limit. He wants them to be safe, too. And he knows he can provide that safety better than anyone else. Eddie is a certified Wilderness First Responder. He knows exactly what to do in the event of a medical emergency in the wilderness. On Tusker Trail’s Kilimanjaro climbs, he and all of his staff are fully prepared to rescue climbers in the event of altitude sickness and other dangers. His skills have been put to the test many times, saving lives on Kilimanjaro, assisting people with oxygen, and monitoring climbers constantly for signs of danger.

He’s even prepared for the extreme, unpredictable situations that are not fixable in the moment. Adverse weather conditions, illness, and people who can’t cope with new surroundings are just a few examples. In East Africa, you can get people to a city and organize a flight home. But in remote areas of Mongolia, it’s not as easy. Which is why he has contracted with a company called Ripcord, who will evacuate travelers from anywhere on Earth. If a problem situation arises, Eddie has it covered.

High Profile

People know Eddie Frank. Lots of them. He’s taken thousands of people on exotic adventures. He has a high profile on Mt. Kilimanjaro, with a reputation for having the best guides, equipment, and training. He employs a small army of dedicated staff members. And he’s aligned himself with numerous charitable causes. With a stellar record like that, I was very curious to hear from others what their experience of working with him was like.

I spoke with his friend Terry, a stockbroker with a keen wit, who met Eddie on a Kilimanjaro charity climb for breast cancer research. Terry said the experience was so positive that they have been arranging charity climbs and climbing together ever since. At first, Terry said Eddie was a hard guy to categorize, but then he came up with the ultimate comparison – Crocodile Dundee! He’s noted that Eddie is a true adventurer, with a lot of insight, and a lot of great stories. He projects an adventurous type of persona – especially with that thick beard of his! He has a keen sense of what he is offering through his business, and he knows that his knowledge and abilities are ultimately what sells his product. He knows he has to be good. Terry recognized from the beginning that Eddie packages fresh modern day adventures, which is rare at a time when many of the great adventures of the world have already been had. He’s believable and credible and that is why people keep coming back to him.

Personal Favorites

When you’ve been so many places, you’re bound to have a few favorites that leave a lasting impression. I asked Eddie what his are and the destinations could not have been more exotic.

He considers sleeping in the crater at 18,700 ft. on Mt. Kilimanjaro, with clear skies and a full moon lighting up the glaciers, a transcendent experience. Not only that, but he met his wife Amy on Kilimanjaro, a formidable mountaineer and emergency medical technician in her own right. For that reason, the mountain is extra special to him. He also counts the Okavango Delta, the Serengeti, the Luangwa Valley, Katavi National Park in East Africa, and Altai Bogd National Park in Mongolia as precious gems of our planet.

Maybe most surprisingly, the few months a year he gets to spend at home and in his office in Lake Tahoe are some of his most precious. He would equally enjoy facing down impetuous buffalo, hippos, or elephants. And he has! More than anything, Eddie wants to provide an eye-opening experience for his customers, show them new cultures, and expand their global world view.

Eddie has his eyes set to the future, and he’s bringing all of his passion and experience with him.

Tusker’s Future

Ask Eddie what’s in store for the future of Tusker Trail and he will answer you with unflinching confidence…

“More remote. Superb guides. Magical places,” is his answer. In Tusker’s case, the future is right now, because adventurers can book trips to two new and wildly exciting destinations. As you read this article, Eddie is scouting the remote corner of western Mongolia for Tusker’s latest trekking adventure. This will be an unbelievable encounter with Kazhak nomads in the Altai Tavn Bogd National Park. This is a place of unspoiled beauty that few people ever get to visit. It will undoubtedly be a transformational experience with exposure to the nomadic Kazakh people, exotic wildlife, and picturesque landscapes. Eddie Frank and a local guide will be on hand to lead the way, with camels in tow.

In addition to new trips, Eddie firmly believes that the success of his company should also be measured by the amount of good it does in the community. So you can expect to see Tusker supporting more and varied worthy causes in the future.

Change Your Life

Eddie designs his treks with one goal in mind – to give his clients an experience that will change their lives, and that he does. His clients tell him time and time again that their Tusker trek was a life-changing experience.

If you’d like to go on an amazing adventure designed by a guy whose name is synonymous with adventure, then check out Eddie Frank’s Tusker Trail. There’s a damn good chance you’ll discover a great deal about the world around you, and no small amount about yourself.