International:

North America:

Menu

THE KINGS OF KILIMANJARO

International:

North America:

- Home

- Kilimanjaro Climb

- Kilimanjaro Planner

- Other Treks

- About Us

- Dates + Prices + Booking

- Contact

International:

North America:

THE KINGS OF KILIMANJARO

International:

Owners & Guides

Eddie Frank, Tusker Trail’s founding guide, was forged in the crucible of Africa’s rugged terrain. From a young age, his father ignited in him a burning passion for adventure that would fuel his lifelong pursuit of the unknown. In 1977 he embarked on a journey of discovery, traversing the African continent and realizing a childhood dream.

Amy Frank, a Canadian native, was also blessed with an unquenchable thirst for adventure. She spent 35 years scaling the highest peaks and leading adventurers through the wild back-country of her homeland. When she joined forces with Eddie, they formed an unstoppable team. Together they have assembled a diverse group of professionals from around the world, all dedicated to the pursuit of the ultimate journey.

Global Staff

Tusker’s trekking team is a force to be reckoned with. Made up of seasoned veterans from all corners of the planet, from the rugged mountains of Nevada to the majestic peaks of Tanzania, the Himalayas of Nepal and the hearty nomads of Mongolia’s far west.

Our focused family is united in a boundless passion for adventure with deep local knowledge. Eddie and Amy have hand-picked each member of the team for their experience and expertise in their respective corners of the world.

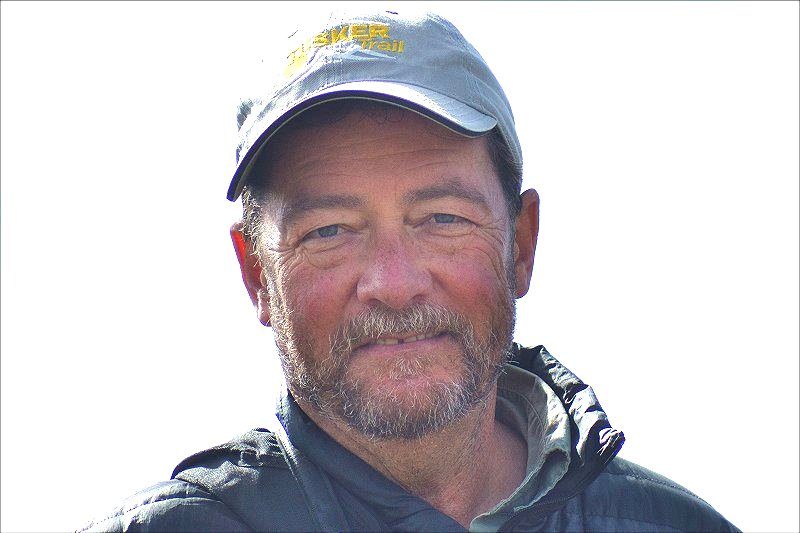

Eddie Frank

Founder, Owner, Guide

Adventurer, explorer and raconteur.

Member of The Explorers Club

Amy Frank

Owner, Guide

Tusker’s guiding light supreme.

Julian Jones

Tanzania Operations Manager

Orchestrates the day to day on Kilimanjaro.

Sarah Jones

Tanzania Managing Director

Decades at the helm at Kilimanjaro.

Katie O’Brien

Head Trekking Coordinator in the USA

Brings your amazing trek together.

Kilimanjaro

An important part of each and every climb.

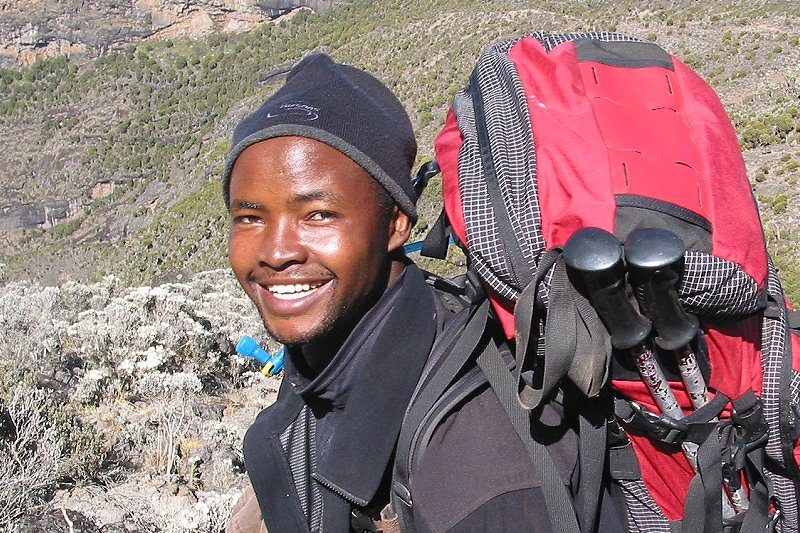

Shabane Hasani

Kilmanjaro and Everest Base Camp Guide

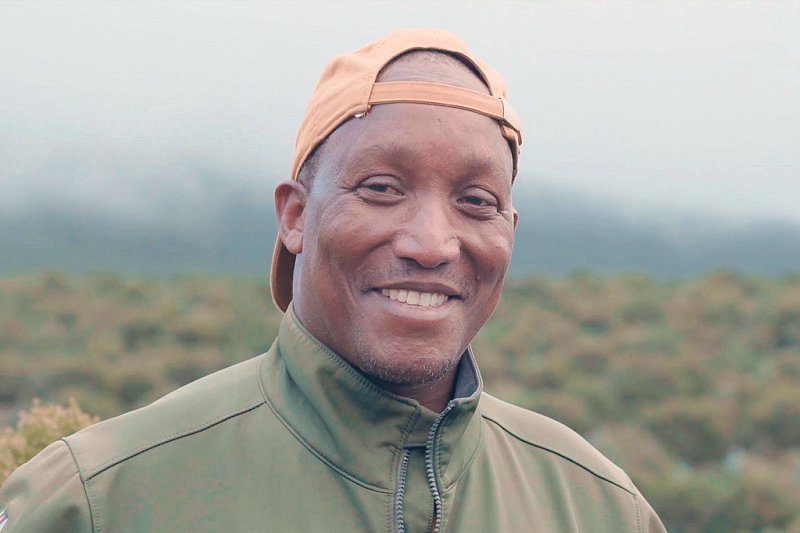

Simon Minja

Kilimanjaro Guide

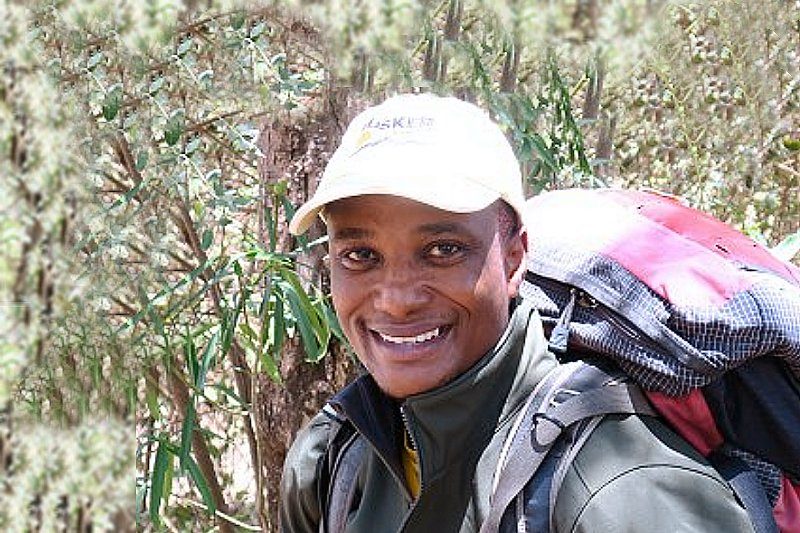

Nemes Meela

Kilmanjaro Guide

Senyaeli Urio

Kilimanjaro Guide

Eliakimu Mashanga

Kilimanjaro Guide

Pastori Minja

Kilimanjaro Guide

Gaudence Kessy

Kilmanjaro Guide

Thobias Meela

Kilimanjaro Guide

Liberaty Matho

Kilimanjaro Guide

Frances Meela

Kilimanjaro Guide

Alex Minja

Kilimanjaro and Mongolia Chef

Our Guest Climbers

We wouldn’t be leading adventures for

48 years without you.

Kilimanjaro Chefs

Masters of the Adventure Kitchen

Trained by the Culinary Insitute of America.

Frank Lulu

Kilimanjaro Equipment Manager

Kilimanjaro Porters

Your Climbing Team

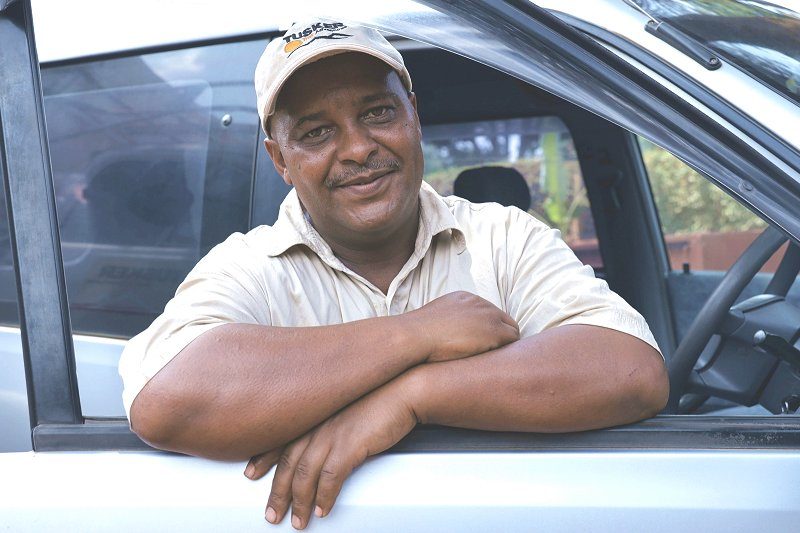

Peter Lulu

Tanzania Driver

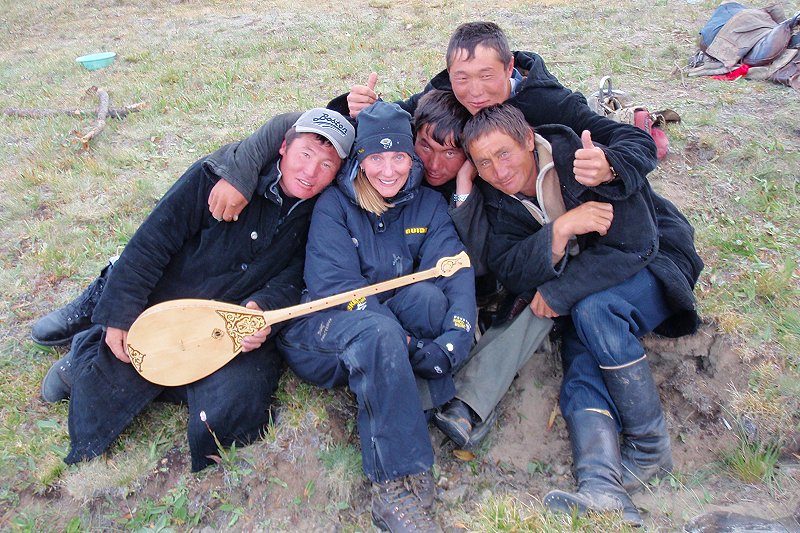

Dosjan

Mongolia Trek Guide

Harmut

Mongolia Trek Horseman

Lister

Mongolia Trek Horseman

Karankai

Mongolia Trek Horseman

Borchak

Mongolia Trek Horseman

Jasai

Mongolia Trek Horseman

Karbai

Mongolia Trek – Head Horse Guide

Alex Minja

Mongolia Chef

Amy and the Horsemen

These guys are essential on your journey.

Att

Eddie’s Boss

Mingma Sherpa

Everest Base Camp Head Guide

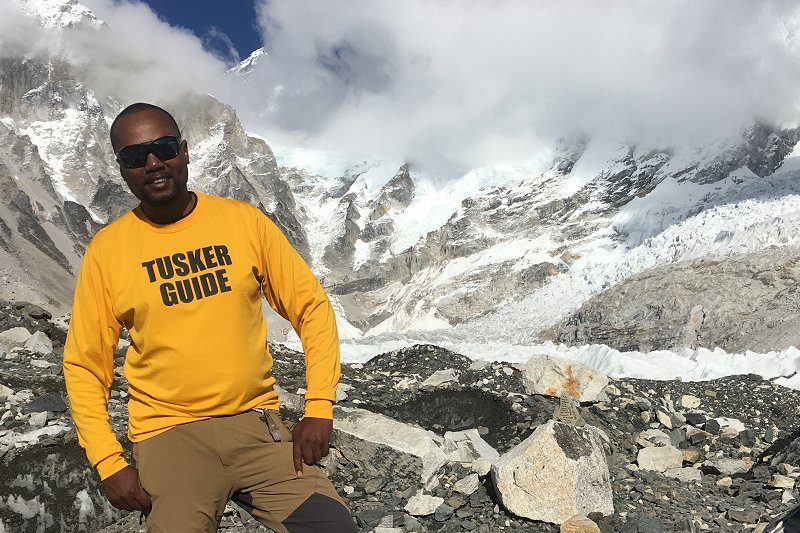

Shabane Hasani

Everest Base Camp Guide

EBC Sherpas

Everest Base Camp Sherpa Team

Happyfrais Kombe

Everest Base Camp Guide

Tusker’s Treks

Now that you have met the Tusker Trail team, start your adventure below.